Lucien Greaves, spokesperson and co-founder of the Satanic Temple, speaks about religious freedom and the After School Satan Club on Sept. 30, 2016, in Kansas City, Mo. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

KANSAS CITY, Mo. (RNS) Lucien Greaves is the Good News Club’s worst nightmare.

Greaves is co-founder of the Satanic Temple, a group dedicated to church-state separation. And his organization’s latest campaign in launching after-school clubs for children, Greaves told RNS before a recent talk in Kansas City, is not so much about indoctrinating children into Satanism — he doesn’t actually believe in the devil as a real being, much less one to be worshipped.

[ad number=”1″]

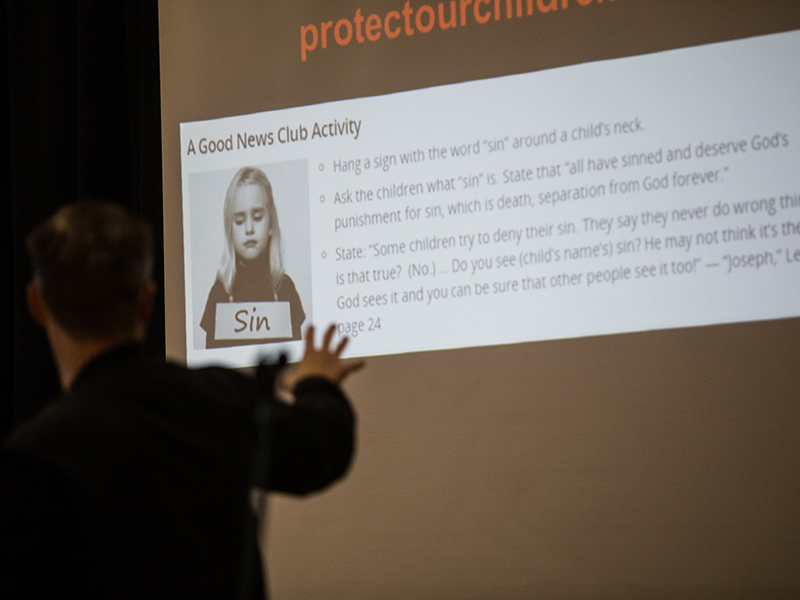

Rather, the After School Satan clubs, as they are called, are about making a statement against the government providing facilities exclusively for Christian after-school programs such as the Good News Club.

A side benefit is that the publicity surrounding the After School Satan clubs is likely to bring far more attention — and maybe public understanding — to the Satanic Temple than anything else the group could do.

Good News Clubs, which are sponsored by the Missouri-based Child Evangelism Fellowship, are a popular Christian after-school club, and in the past decade they have become increasingly common in schools across the U.S. During club time, children are taught Bible lessons, sing songs, play games and hear missions stories.

After a 2001 Supreme Court ruling that allowed conservative Christian clubs to organize in grade schools, the number of Good News Clubs — named after the “good news” of the Gospel — spiked to more than 3,500, and they are present in more than 5 percent of the nation’s public elementary schools.

That growth both irked Greaves and provided a blueprint for the Satanic Temple, which is seeking to establish After School Satan clubs in cities such as Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.

[ad number=”2″]

Not surprisingly, the effort has run into resistance from some local school officials, Greaves said, and opposition in Tucson, Ariz., is so stiff that it could eventually lead to legal action.

But organizers have also had some success, and the first club is set to start this month, on Wednesday (Oct. 19) in Portland, Ore.

“Any school can reasonably reject certain subject matter,” said Greaves, 40. “What they can’t do is allow some religious after-school clubs and reject others. Then you are actually dealing in viewpoint discrimination.”

RELATED: Florida city council may halt opening prayers to stop Satanist’s invocation

The After School Satan website says its club will include lessons on science and reason, with a “focus on free inquiry and rationalism,” and will also have fun activities.

If the appearance of these clubs might prompt concern from some, religious liberty advocates whose legal efforts made way for the Good News Clubs know they can’t stand in the way.

“I would definitely oppose after-school Satanic clubs, but they have a First Amendment right to meet,” Mat Staver, head of the Liberty Counsel, told The Washington Post in July.

“I suspect, in this particular case, I can’t imagine there’s going to be a lot of students participating in this. It’s probably dust they’re kicking up and is likely to fade away in the near future for lack of interest.”

But conservative believers aren’t the only ones who might look askance at the Satanic Temple and its after-school clubs.

Greaves’ host for this talk was the Kansas City Atheist Coalition, and atheists aren’t necessarily keen on the idea of something that seems to promote any religion — be it satanic or Christian.

About 80 people gathered to hear Lucien Greaves, spokesperson and co-founder of the Satanic Temple, speak about religious freedom on Sept. 30, 2016, in Kansas City, Mo. The event was hosted by the Kansas City Atheist Coalition. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

Introducing Greaves to about 80 people gathered for the event, atheist coalition president Joshua Hyde sought to put that issue to rest quickly, saying he first wanted to address “the elephant in the room.”

Since announcing the event, Hyde said, he had received several inquiries questioning the relationship between the two organizations.

“Our mission is to cultivate a positive secular community and to work with organizations toward a common goal,” he explained.

Although the groups have fundamental differences, he added, “they share a common goal: the nonpreferential treatment of citizens by our government regardless of what they do or do not believe.”

There certainly appeared to be some crossover between the two groups.

Several people in the crowd wore T-shirts and buttons printed with the Satanic Temple logo, even if there was some lingering unease over identifying as a Satanist.

Mike Ryberg, an atheist who identifies with the Satanic Temple’s philosophical approach, drove two hours from Columbia, Mo., to see Lucien Greaves speak in Kansas City, Mo., on Sept. 30, 2016. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

“I’m atheist, but I identify with TST’s philosophical approach,” said Mike Ryberg, who joined the Satanic Temple in 2014 and drove two hours from Columbia, Mo., to attend the event.

Adam, a Kansas City native who preferred not to use his last name, called himself an “admirer” of the Satanic Temple.

“They’re not Satanists, they’re atheists. I’m not a Satanist, I’m an atheist. It’s a ploy to bedevil Christians and it invariably works,” he said.

Free buttons that read “Godless Government” are offered during a gathering with the Kansas City Atheist Coalition and the Satanic Temple to discuss religious freedom on Sept. 30, 2016, in Kansas City, Mo. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

This is how Greaves explained it: “People miss that the self-identified Satanist isn’t merely doing this for the shock value that it provokes among Christians – it very much is a personal statement, a personal declaration of independence against those things they feel oppressed by.”

The invention of Lucien Greaves

Born Doug Mesner to a Protestant mother and Catholic father, Greaves grew up in Detroit and was raised in both Christian traditions. The few times he visited a Catholic Church, he said, he found it “horrifying.”

Greaves didn’t much like Protestant teaching, either, and still recalls the message of a Sunday school song called “Careful Little Eyes.” He describes the song as a warning that we are “being looked upon and judged by [an] ultimate tyrant in the sky.”

The lyrics advise kids to be careful what they see, hear, do with their hands, do with their feet, and what they say, for “There’s a Father up above/And He’s looking down in love.”

Then, during his youth, Greaves grew outraged by the cultural phenomenon known as “the Satanic Panic” of the 1980s and 1990s.

Lucien Greaves, spokesperson and co-founder of the Satanic Temple, finds a caterpillar in the backyard of a friend’s home in Lenexa, Kan., on Sept. 30, 2016. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

That wave of moral panic grew out of a widespread fear, especially among conservative believers, “that satanic forces were taking over the country,” he said.

Movies such as “The Exorcist” and “Rosemary’s Baby,” as well as heavy metal music, were often blamed for fueling the Satanic Panic.

For Greaves, the combination of his rejection of his religious upbringing and what he saw as the damage wrought on people’s lives by the hysteria over Satanism spurred him to co-found the Satanic Temple four years ago in Salem, Mass., where he lives — aptly enough, the city that is infamous for the 17th-century witch trials.

At the same time, he needed to start a Facebook page for the Satanic Temple under a personal name, and so Doug Mesner became Lucien Greaves — at least in the public sphere.

What do Satanists believe anyway?

Lucien Greaves, spokesperson and co-founder of the Satanic Temple, speaks about religious freedom on Sept. 30, 2016, in Kansas City, Mo. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

But if Lucien Greaves is an invented name — he is vague about exactly why he chose it — is Satanism a made-up religion?

Some people think that Satanists are just atheists who want attention, so they label themselves in a shocking way. Others are just plain scared of them.

“We are an atheistic religion,” Greaves explained. “Our subculture is not dependent on a belief in a literal Satan.”

Greaves admits that some people think the Satanic Temple is merely a prank and that its activism is simply meant to shock the general population.

[ad number=”3″]

But there is a coherence to Satanism, according to Greaves, as a tradition that grew out of literature and poetry and as “an amalgamation of many other religious beliefs.”

“We believe strongly in religious plurality. Our point hasn’t been to keep any one religion out of the public forum. But when you do set up a public forum, you have to realize that you’ve opened it up to all points of view.

“Once you have this utopian notion that if everybody conforms to your specific religious beliefs, that the world would be a better place – that’s when ugly things start happening,” he added.

Mike Ryberg, an atheist who identifies with the Satanic Temple’s philosophical approach, wears buttons from the the group, on Sept. 30, 2016. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

So why choose Satan as a symbol?

Of course, by choosing to use Satan as their namesake and in visual representations of themselves, members of the Satanic Temple open themselves up to some sharp criticism.

Greaves expects to be misunderstood, but his mission is to convince people that self-identified Satanists are solid members of the community.

“If people can see that Satanists aren’t immoral or criminal or cruel, we have forced them to judge others based on real-world actions rather than maintain some obscure out-group standard by which unjustified purges have always taken place,” he said.

But more than just surviving as a misunderstood minority, the Satanic Temple does see a chance for serious growth. Greaves estimates the group’s current membership to be around 50,000, with chapters nationwide, and soon to add more chapters overseas.

For one thing, the number of religiously unaffiliated Americans, the so-called nones, continues to grow. And the current presidential campaign, and the uses and misuses of religion it has brought, might draw more converts to Greaves’ cause.

But serious as the church-state issues are, the Satanic Temple also wants to have a little fun.

Barbara Williams, from Basehor, Kan., poses for a photo with Lucien Greaves, the spokesperson and co-founder of the Satanic Temple, in Kansas City, Mo., on Sept. 30, 2016. RNS photo by Sally Morrow

“I don’t want us to be an organization that feels this criticism profoundly enough that perhaps we’re not legitimized as a religion because we’re not solemn and sober enough – that we feel we have to take the fun or the humor out of any of the activities we do,” Greaves said.

“Naturally, people who identify with Satanism usually have a more Gothic aesthetic or darker humor,” he continued. “But I also wouldn’t want us to shy away from the prettier things.”

As for the election, Greaves didn’t take sides — Satanists, like atheists, come in all political stripes, and many are attracted to a libertarian creed.

But he admitted his fear of today’s Republican Party.

“More and more, this tawdry marriage of the GOP to far-right Christian evangelicalism is alienating a lot of libertarian conservatives who are less hypocritical about their adherence to constitutional values,” he says.